Literature

Categories

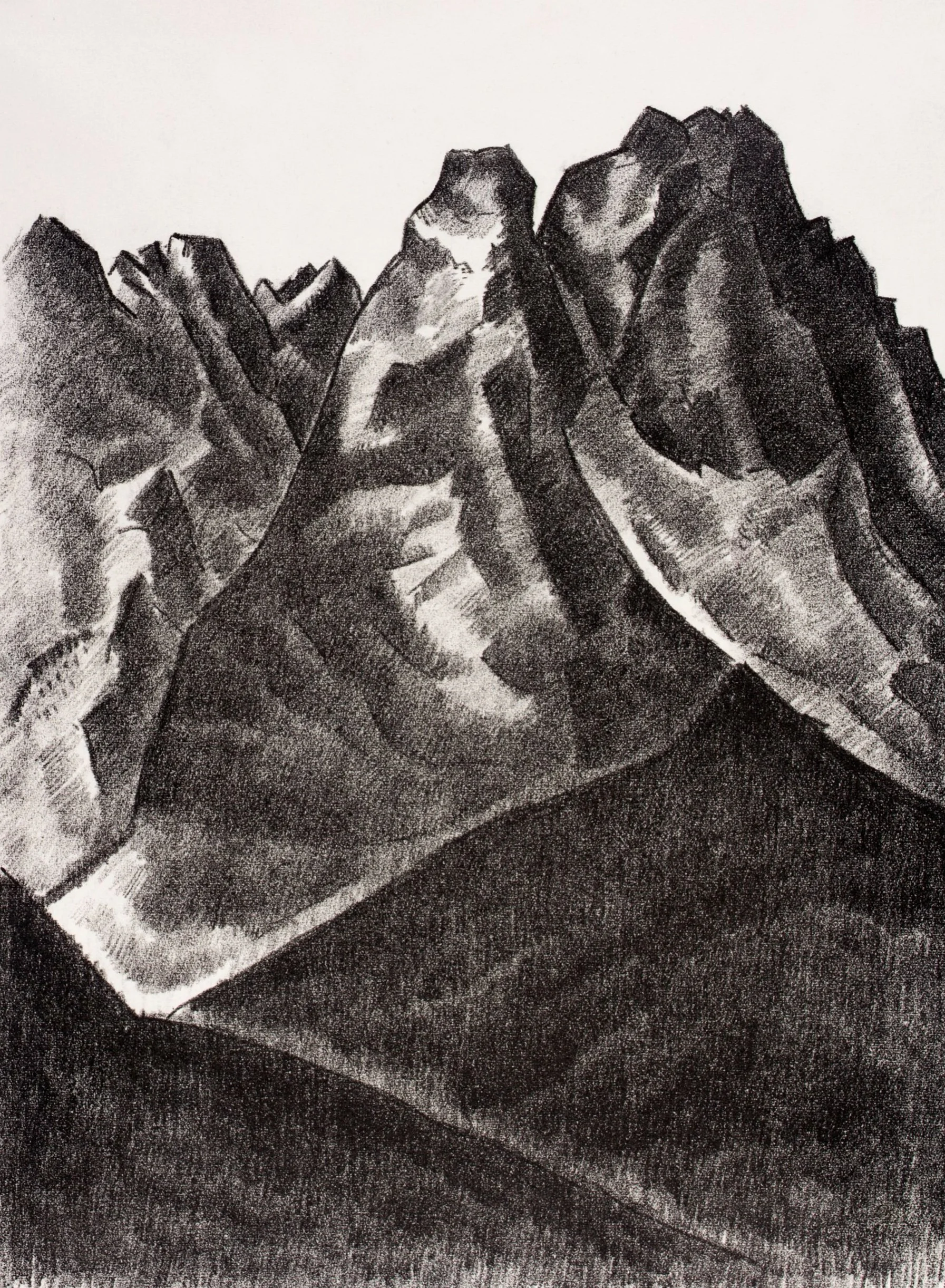

The Blizzard

Pushkin unfolds a tale of fate and farce, where miscommunications and misfired intentions dance through a snowbound night with operatic irony. What begins as a romantic elopement collapses into absurdity, only to resolve years later with a twist as swift and cold as the storm that started it.

Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad

M.R. James conjures a ghost story not with gore, but with the mounting dread of the unseen—where rational inquiry and antiquarian fussiness unravel beneath the weight of something elemental and malign. The whistle, once blown, does not summon affection but awakens a presence stitched from wind, sand, and sleep-disturbed terror.

The Red Room

Wells dismantles the machinery of the classic haunted house, revealing not specters but the psychology of fear itself—how darkness breeds dread, and dread conjures its own ghosts. The room remains unchanged; it is the mind that flickers, extinguishes, and relights in terror.

Two Thanksgiving Day Gentlemen

O. Henry serves up a wry, melancholic feast in this portrait of ritual charity and quiet hunger, where tradition masks necessity and generosity walks hand in hand with pride. In just a few turns of his well-laced prose, sentiment curdles into irony—and back again—without ever losing the ache beneath the surface.

John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving

Hawthorne stages a Thanksgiving reunion suffused with warmth, shadow, and moral ambiguity, as a wayward daughter returns home not for absolution, but for a fleeting resurrection of the self she once was. In a tale where firelight and familial grace briefly hold darkness at bay, the parting is inevitable, and final, as sin reasserts its claim with a chilling clarity only Hawthorne dares render so gently.

The Rider of the Black Horse

In Lippard’s feverish, apocalyptic vision of Revolutionary America, the Black Horseman rides not merely as courier but as omen—his midnight gallop through storm and battle summoning the specter of a nation both birthed and haunted by violence. At once allegory and gothic spectacle, the tale gallops headlong into the sublime terror of liberty forged in blood.

The Skull

In this taut meditation on time, violence, and fatalism, Philip K. Dick dispatches a man into the past to commit murder, only to find that the skull he carries is his own. The Skull is a recursive fable about destiny disguised as pulp, where free will stumbles over paradox and history writes itself in bone.

Clay

In Clay, James Joyce compresses a life’s quiet desolation into a single evening, where small kindnesses, awkward silences, and a forgotten song trace the outline of a woman long faded into habit and half-regarded charity. The story haunts not with tragedy, but with the muffled weight of things unsaid, and the soft, persistent erosion of time.

A Little Cloud

A chance reunion stirs something restless in Little Chandler, whose quiet life begins to feel suddenly—and permanently—too small. In Joyce’s hands, domesticity and ambition clash not in crisis, but in quiet humiliations, where the poetry remains unwritten and the baby’s cry drowns out the last note of hope.

Young Goodman Brown

Beneath the trembling pines and flickering torches of Hawthorne’s dark forest, a young man’s night journey becomes a grim initiation into the duplicity of the human soul. What he returns with is not proof of sin or innocence, but something crueler: the inability to trust either again.

One Autumn Night

In a sodden corner of the city’s edge, Gorky stages a night not of salvation, but of fleeting human warmth—where two outcasts share a crust of bread, a sliver of comfort, and the unbearable weight of knowing how little separates pity from grace. The story never pleads for sympathy, yet leaves its mark like rain soaking through a thin coat: slowly, deeply, and with a chill that lingers long after morning.

The Walls Are Falling

A cold revolutionary finds himself, in his final hours, not embittered but transfigured—liberated from fear, weariness, and contempt as death draws near. In one of Andreyv’s most luminous psychological portraits, walls dissolve, time loosens, and the soul expands toward a terrible and tender clarity, where even the doomed become radiant with love.

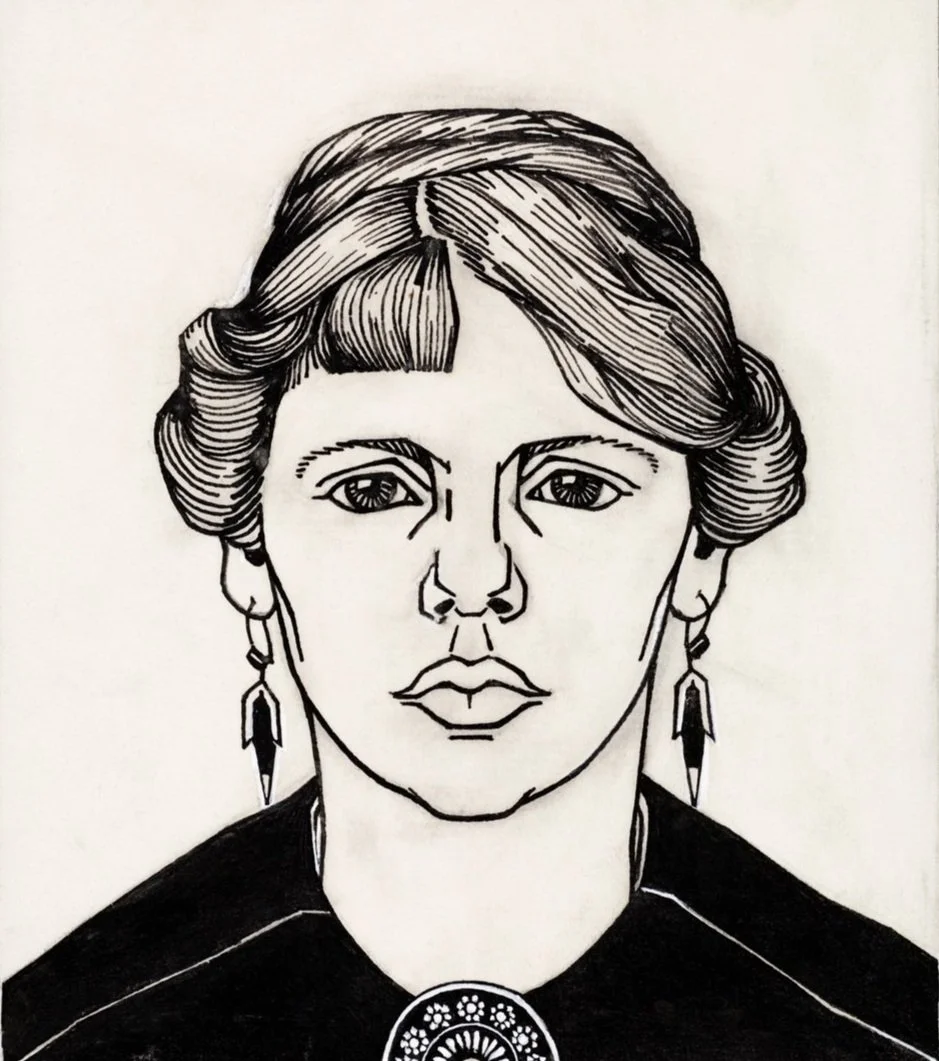

A New England Nun

Louisa Ellis has spent fourteen quiet years tending to her home, her habits, and her solitude, an order so finely calibrated that even the clink of a suitor's teacup feels like a trespass. Wilkins crafts a story as crisp and deliberate as Louisa’s routines, where renunciation is not sacrifice but a subtle, radical act of self-preservation.