Literature

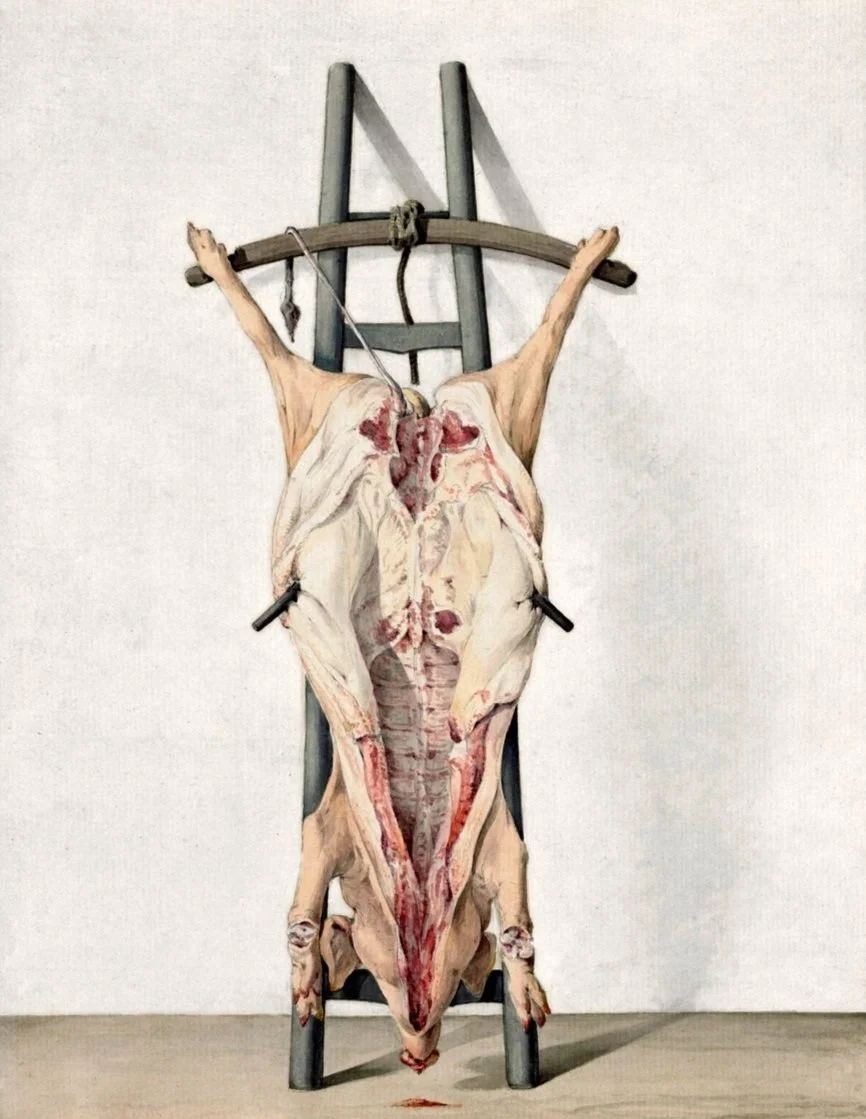

First published in The Children’s Book of Thanksgiving Stories in 1915, this French fairy tale by P. J. Stahl tells of a kingdom so obsessed with sweets that their king orders a colossal tart to satisfy them, only for indulgence to bring ruin. A gently comic lesson in moderation and gratitude.

In Fannie Wilder Brown’s The Thanksgiving Goose, a boy’s complaints about his Thanksgiving dinner lead him to a neighbor’s bustling kitchen, where a family with little to spare is joyfully making mince pies. Their simple gratitude teaches him a quiet lesson in thankfulness, just in time for the holiday.

Set in the damp heart of Providence, The Shunned House unfolds as both antiquarian mystery and metaphysical horror: a scholar and his uncle trace a lineage of decay to the cellar of an old home, where something beyond science feeds on human life. Lovecraft turns local history and rational inquiry into instruments of dread, ending with a quiet, corrosive triumph that feels less like victory than survival.

A strange shop appears on Regent Street, offering real magic, but only to the right sort of child. In this hauntingly playful tale by H. G. Wells, a boy and his father cross the threshold into a world where toys come to life and reality folds in on itself. The trick, it seems, is deciding what to believe once you're back outside.

Dickens’s 1859 Christmas “haunted house” turns out to be less about specters than about how rumor and memory haunt the living. A skeptical narrator debunks village frights and, in Master B.’s garret, meets the truest ghost of all.

A grand seaside hotel once filled with gaiety, the Old Mansion fell into ruin after a tragic shipwreck, whispers of looted dead, and ghostly visions of drowned mothers and children. Today, only charred timbers and haunted memory linger on the dunes of Long Beach.

In Thanksgiving Day, Ambrose Bierce strips the holiday of sentiment and reveals its moral hollowness, turning the ritual of pardon into a grim spectacle of irony and injustice. With characteristic venom, he exposes a society eager to pat itself on the back for mercy only after indulging fully in cruelty, a feast of self-congratulation served cold.

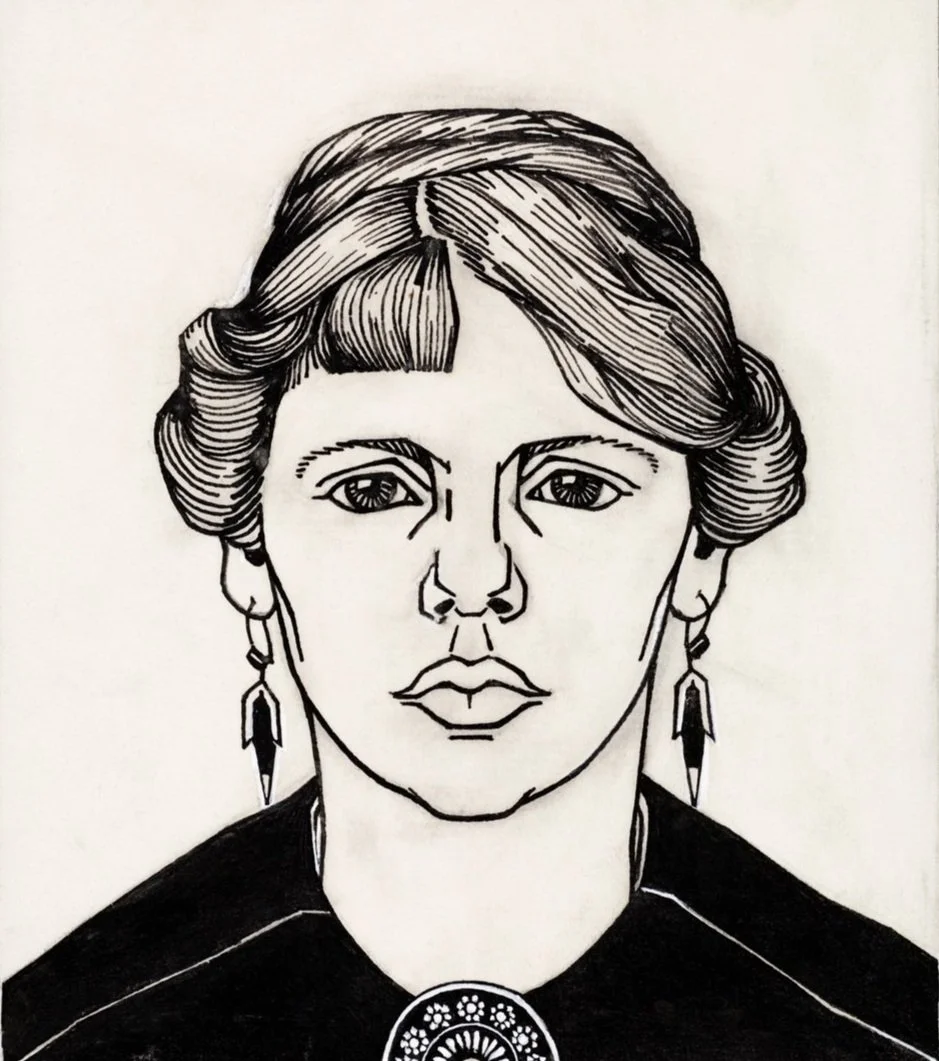

In The Man with the Book, a pivotal early chapter in The Witch of Salem, John R. Musick conjures a spectral figure whose cryptic presence haunts both the colonial landscape and the conscience of its people. Neither wholly allegorical nor entirely human, he embodies the uneasy fusion of religious zeal and retributive justice that drives the Salem trials forward—his silent authority casting a longer shadow than any spoken curse.

In Howe’s Masquerade, one of the more allegorical tales from Twice-Told Tales, Hawthorne stages a spectral procession of America’s past within the ballroom of Boston’s Province House, blurring the line between revelry and reckoning. Cloaked in historical costume and moral unease, the tale reflects Hawthorne’s preoccupation with the haunted legacy of the Puritan past and the theatricality of national identity.

In Cheap Knowledge, a quietly elegiac essay from Pagan Papers, Kenneth Grahame pays tribute to the humble delights of secondhand bookstalls, where faded volumes whisper of forgotten owners and half-remembered dreams. With characteristic charm and a touch of wistfulness, he elevates the act of browsing cast-off books into a celebration of democratic intellect—where wisdom, once costly, is scattered like autumn leaves for any wanderer to claim.

Mark Twain turns a simple boyhood anecdote into a sly meditation on pride, gullibility, and the enduring comedy of self-deception. What begins as a rustic tale of pursuit and ambition ends, in classic Twain fashion, with the narrator hoisted by his own hubris—outwitted not by man, but by bird.

John Kendrick Bangs transforms suburban domestic life into farce, charting one father’s descent from hopeful holiday rest to bruised, bedraggled chaos at the hands of an overzealous son and a rogue football. Beneath the slapstick lies a sharp, affectionate satire of middle-class aspiration, parental exhaustion, and the quietly heroic art of enduring family life with humor intact.

In The Witch, Anton Chekhov delivers a brief, charged encounter between a provincial postmaster and his wife during a violent snowstorm, where suspicion, sensuality, and superstition swirl with the wind outside. What begins as a domestic quarrel mutates into something more elemental, as Chekhov exposes the undercurrents of fear and longing that haunt even the most ordinary lives.

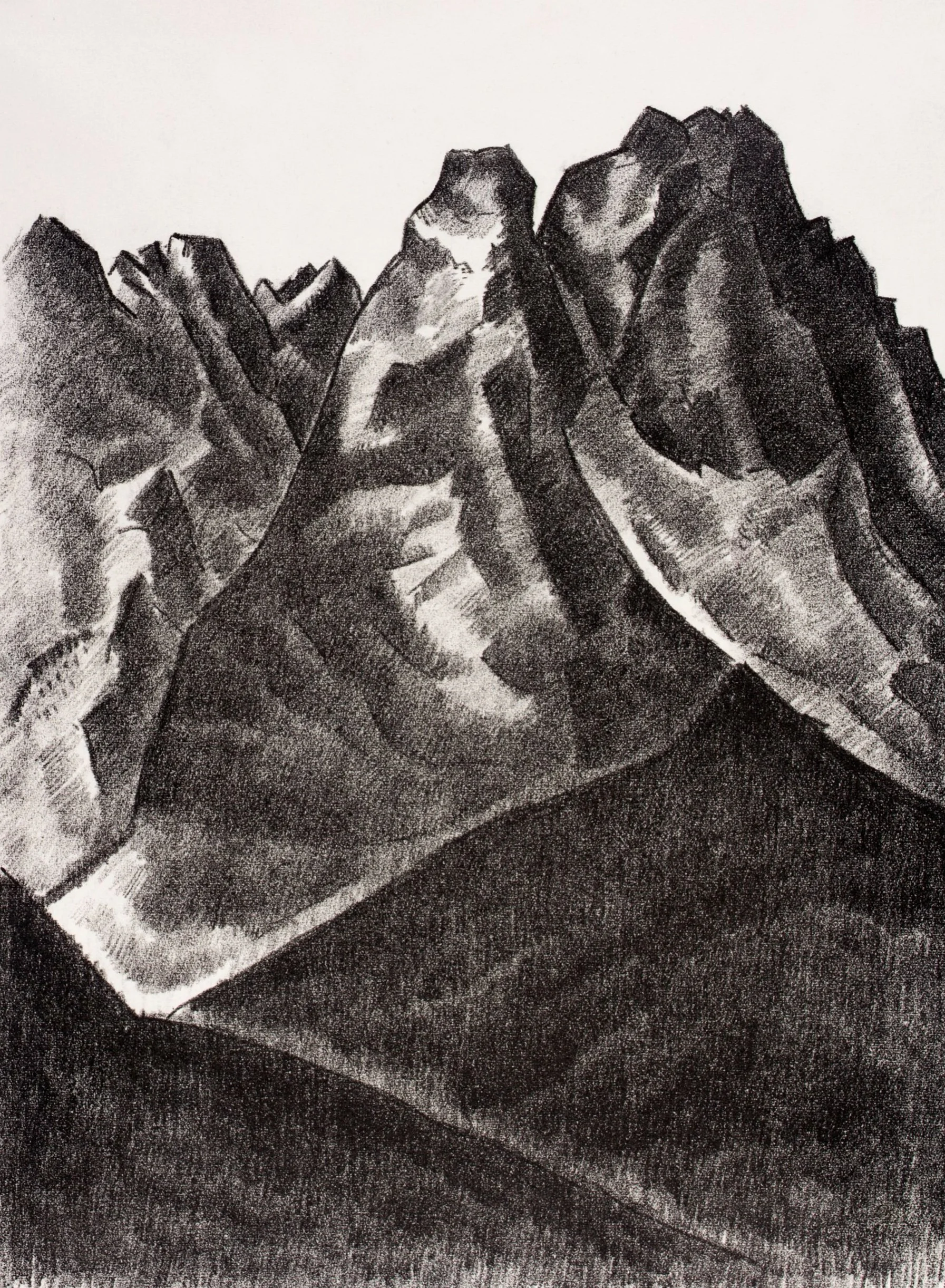

Algernon Blackwood conjures a tale of quiet terror and metaphysical unease, as a solitary camper’s idyllic retreat on a deserted island becomes a confrontation with something ancient, watchful, and unseen. With his signature restraint and reverence for the natural world, Blackwood blurs the line between landscape and spirit, suggesting that the most haunting presences are those that remain unnamed.

In The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Washington Irving blends folklore, satire, and gothic atmosphere to conjure a distinctly American ghost story, one where superstition cloaks social rivalry, and the specter of the Headless Horseman becomes a mirror for colonial anxieties and masculine bravado. Beneath its autumnal charm and haunted valleys lies a tale less about terror than about the stories we tell to disguise ambition and defeat.

In The Living Death, Ferenc Molnár constructs a hushed, fevered horror in which the dead are not resurrected but awakened—only to discover that returning to life is the one thing truly forbidden. Beneath its gothic trappings, the story becomes a meditation on alienation, exhaustion, and the moral weight of choosing between memory and oblivion.

Crisp with lark-song and the scent of fallen leaves, An Autumn Effect wanders through back roads and beech woods, observing the world with a light, amused eye and an undercurrent of melancholy. Stevenson lingers not to analyze but to feel—capturing the glow before dusk, the charm of small towns, and the gentle absurdity of both donkeys and men.

What begins as a routine cargo manifest spirals into an ontological standoff between appetite and awareness, as the crew of a Martian freighter confronts the unsettling eloquence of their dinner. With serene authority, the Wub disarms its captors—not through power, but by revealing how little they understand the difference between consuming and being consumed.

Time folds quietly in this story, where literary memory, travel fatigue, and spectral suggestion converge in a single, tepid plunge. More hallucination than haunting, the tale lingers in the space between homage and invention, offering a ghost not of the dead, but of the books we carry with us.

Richard Garnett’s The Twilight of the Gods and Other Tales is a sparkling collection of literary curiosities—fables, fantasies, and philosophical vignettes—that revel in the absurdities of gods, men, and the tenuous line between them.

M.R. James conjures a ghost story not with gore, but with the mounting dread of the unseen—where rational inquiry and antiquarian fussiness unravel beneath the weight of something elemental and malign. The whistle, once blown, does not summon affection but awakens a presence stitched from wind, sand, and sleep-disturbed terror.

Wells dismantles the machinery of the classic haunted house, revealing not specters but the psychology of fear itself—how darkness breeds dread, and dread conjures its own ghosts. The room remains unchanged; it is the mind that flickers, extinguishes, and relights in terror.

O. Henry serves up a wry, melancholic feast in this portrait of ritual charity and quiet hunger, where tradition masks necessity and generosity walks hand in hand with pride. In just a few turns of his well-laced prose, sentiment curdles into irony—and back again—without ever losing the ache beneath the surface.

Hawthorne stages a Thanksgiving reunion suffused with warmth, shadow, and moral ambiguity, as a wayward daughter returns home not for absolution, but for a fleeting resurrection of the self she once was. In a tale where firelight and familial grace briefly hold darkness at bay, the parting is inevitable, and final, as sin reasserts its claim with a chilling clarity only Hawthorne dares render so gently.

In Lippard’s feverish, apocalyptic vision of Revolutionary America, the Black Horseman rides not merely as courier but as omen—his midnight gallop through storm and battle summoning the specter of a nation both birthed and haunted by violence. At once allegory and gothic spectacle, the tale gallops headlong into the sublime terror of liberty forged in blood.

In this taut meditation on time, violence, and fatalism, Philip K. Dick dispatches a man into the past to commit murder, only to find that the skull he carries is his own. The Skull is a recursive fable about destiny disguised as pulp, where free will stumbles over paradox and history writes itself in bone.

In Clay, James Joyce compresses a life’s quiet desolation into a single evening, where small kindnesses, awkward silences, and a forgotten song trace the outline of a woman long faded into habit and half-regarded charity. The story haunts not with tragedy, but with the muffled weight of things unsaid, and the soft, persistent erosion of time.

Beneath the trembling pines and flickering torches of Hawthorne’s dark forest, a young man’s night journey becomes a grim initiation into the duplicity of the human soul. What he returns with is not proof of sin or innocence, but something crueler: the inability to trust either again.

In a sodden corner of the city’s edge, Gorky stages a night not of salvation, but of fleeting human warmth—where two outcasts share a crust of bread, a sliver of comfort, and the unbearable weight of knowing how little separates pity from grace. The story never pleads for sympathy, yet leaves its mark like rain soaking through a thin coat: slowly, deeply, and with a chill that lingers long after morning.

A cold revolutionary finds himself, in his final hours, not embittered but transfigured—liberated from fear, weariness, and contempt as death draws near. In one of Andreyv’s most luminous psychological portraits, walls dissolve, time loosens, and the soul expands toward a terrible and tender clarity, where even the doomed become radiant with love.

In this Victorianized Icelandic fairy tale, two fugitives find refuge on an enchanted island ruled by dwarfs and a sorrowful giantess, whose world unravels the moment a Christian blessing crosses the air. The result is a fascinating blend of Norse supernatural lore reshaped by 19th-century Christian sensibilities.

A sweeping look at Demeter’s evolution from earth-mother to goddess of agriculture, this excerpt traces her central role in Greek myth, from the abduction of Persephone to the origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries, revealing how ancient storytellers used her tale to explain the seasons, civilization, and the promise of rebirth.

In Perrault’s Donkey-Skin, the grotesque and the marvelous collide: a princess, pursued by her father’s delusion, cloaks herself in a beast’s hide and vanishes into obscurity. She keeps her splendor hidden until a ring, slipped unnoticed into a cake, reveals her secret and restores her to love, dignity, and a rightful place in the world.

Categories

Beyond Lies the Wub

What begins as a routine cargo manifest spirals into an ontological standoff between appetite and awareness, as the crew of a Martian freighter confronts the unsettling eloquence of their dinner. With serene authority, the Wub disarms its captors—not through power, but by revealing how little they understand the difference between consuming and being consumed.

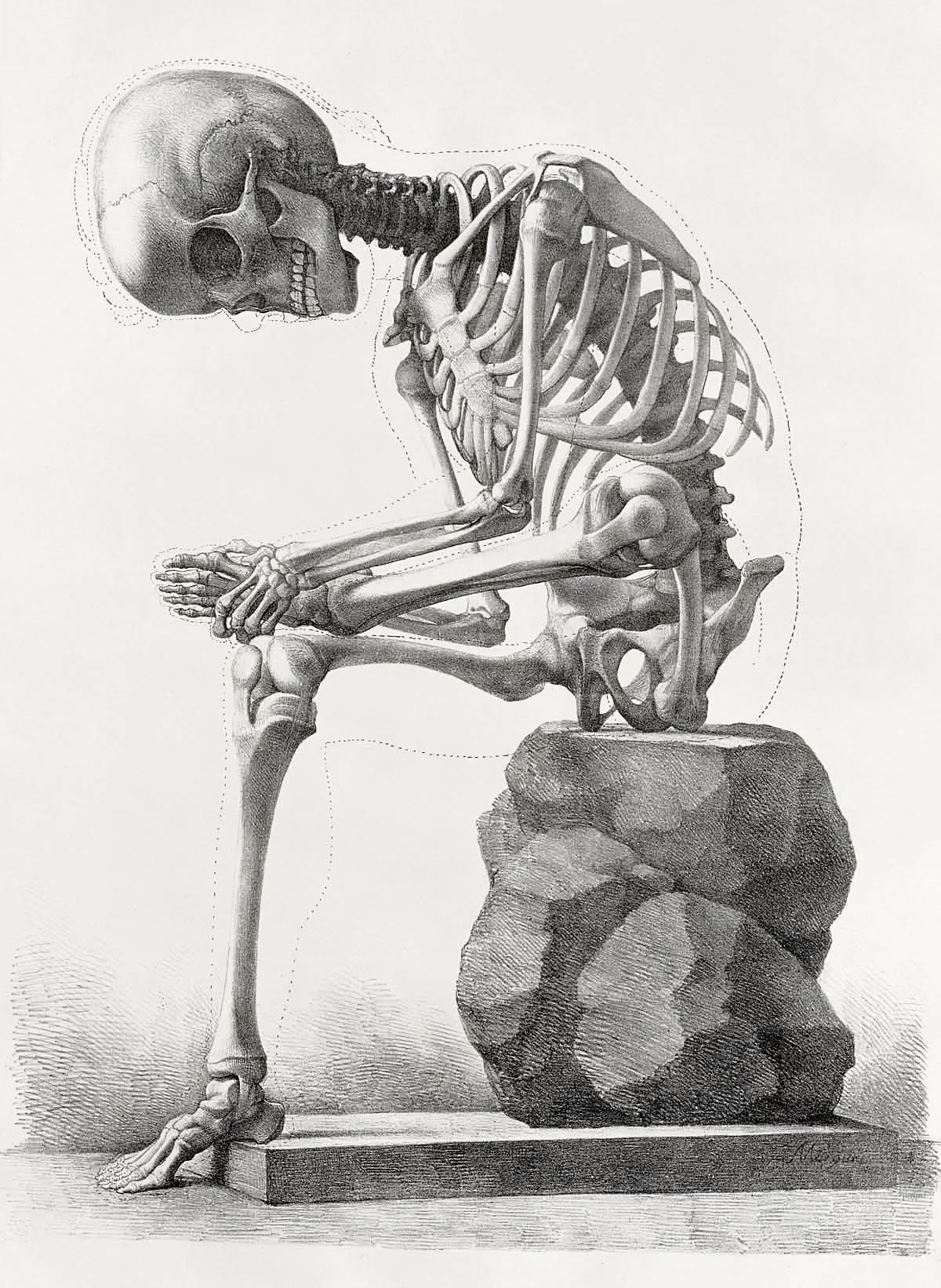

The Skull

In this taut meditation on time, violence, and fatalism, Philip K. Dick dispatches a man into the past to commit murder, only to find that the skull he carries is his own. The Skull is a recursive fable about destiny disguised as pulp, where free will stumbles over paradox and history writes itself in bone.