A Christmas Tree

Dickens’s “A Christmas Tree” wanders through the ornaments of childhood memory, using the Christmas tree as a symbolic ladder from toys to tales to ghostly imaginings and finally to spiritual reflection. It’s a dreamy, nostalgic essay that captures how Christmas gathers together wonder, fear, and hope across a lifetime.

What Christmas Is As We Grow Older

Dickens meditates on how the meaning of Christmas deepens with age, expanding beyond youthful fantasy into a season of remembrance, compassion, and forgiveness. He urges readers to “shut out nothing,” embracing joy and sorrow alike as part of the holiday’s enduring humanity.

The Kingdom of the Greedy

First published in The Children’s Book of Thanksgiving Stories in 1915, this French fairy tale by P. J. Stahl tells of a kingdom so obsessed with sweets that their king orders a colossal tart to satisfy them, only for indulgence to bring ruin. A gently comic lesson in moderation and gratitude.

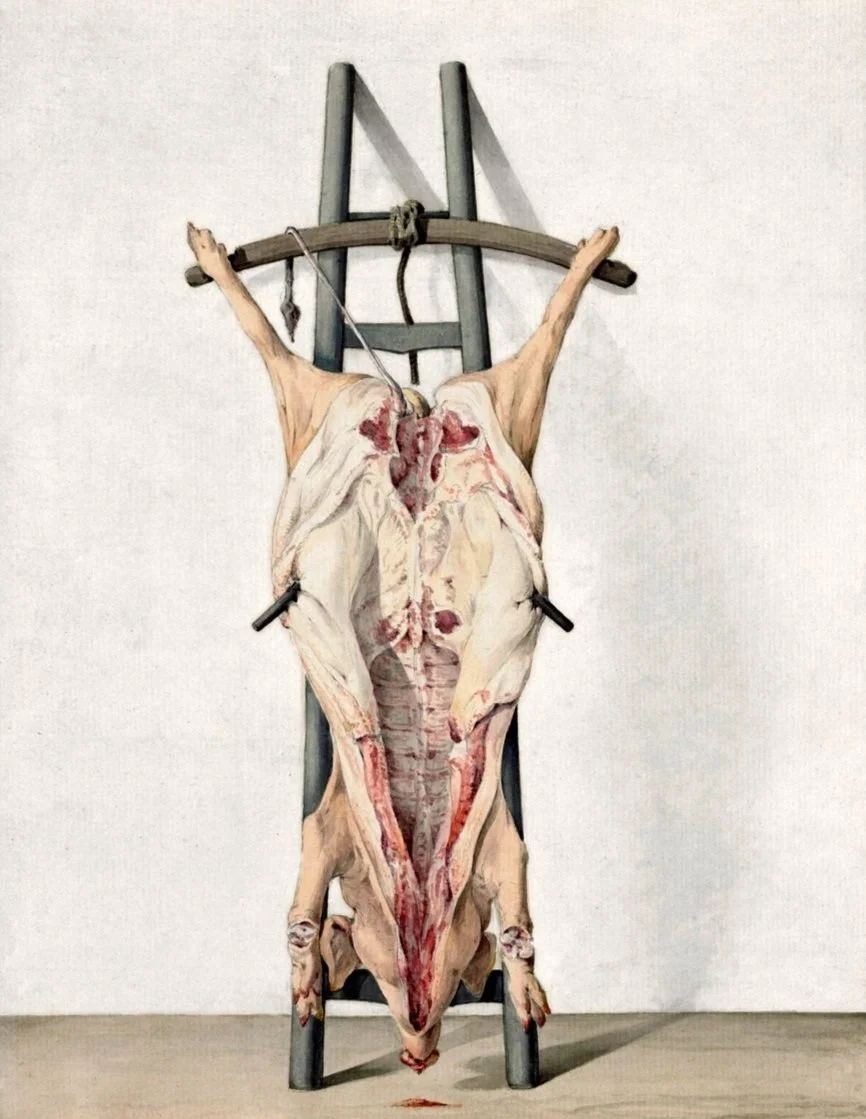

The Thanksgiving Goose

In Fannie Wilder Brown’s The Thanksgiving Goose, a boy’s complaints about his Thanksgiving dinner lead him to a neighbor’s bustling kitchen, where a family with little to spare is joyfully making mince pies. Their simple gratitude teaches him a quiet lesson in thankfulness, just in time for the holiday.

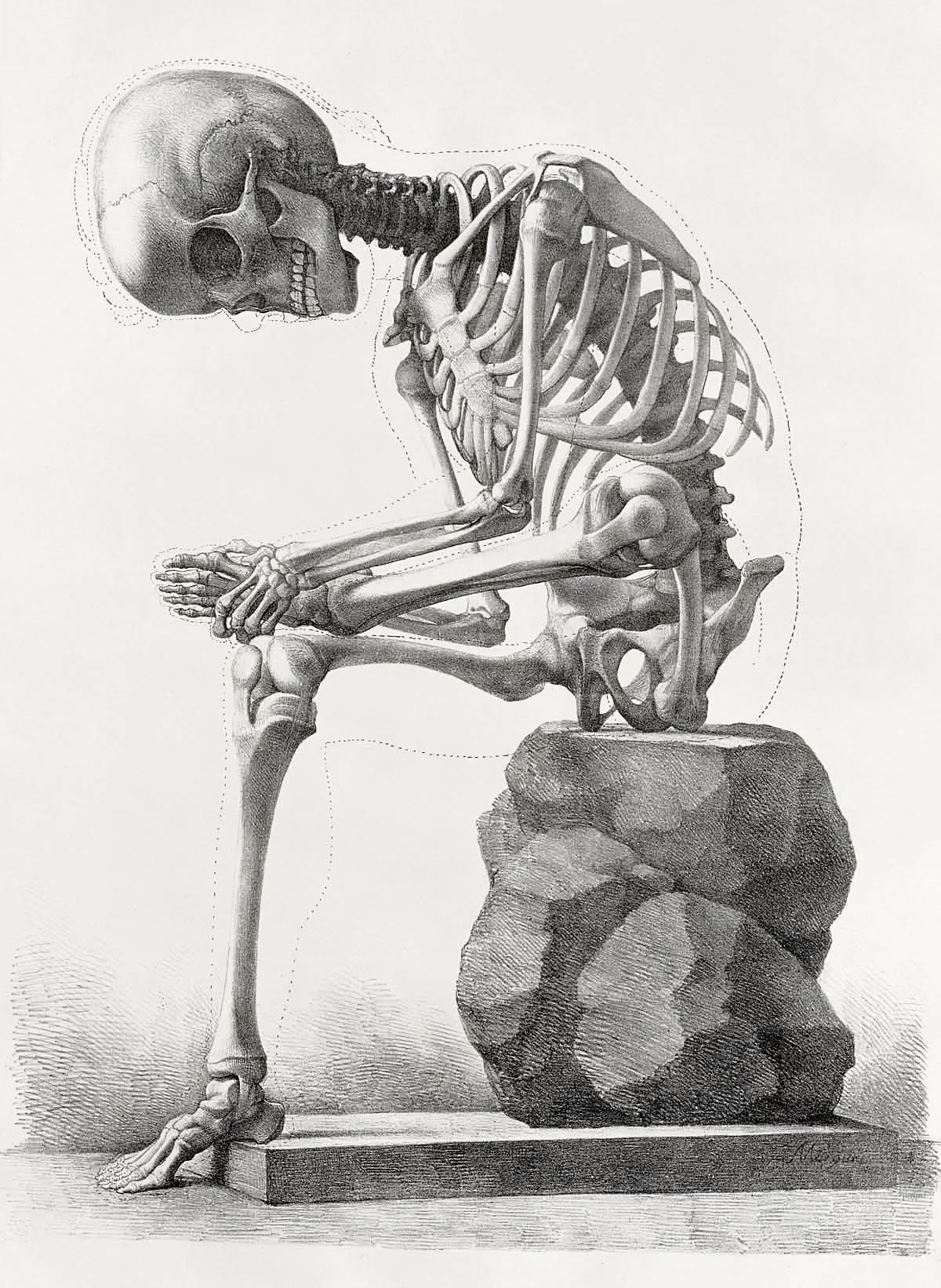

The Shunned House

Set in the damp heart of Providence, The Shunned House unfolds as both antiquarian mystery and metaphysical horror: a scholar and his uncle trace a lineage of decay to the cellar of an old home, where something beyond science feeds on human life. Lovecraft turns local history and rational inquiry into instruments of dread, ending with a quiet, corrosive triumph that feels less like victory than survival.

The Magic Shop

A strange shop appears on Regent Street, offering real magic, but only to the right sort of child. In this hauntingly playful tale by H. G. Wells, a boy and his father cross the threshold into a world where toys come to life and reality folds in on itself. The trick, it seems, is deciding what to believe once you're back outside.

The Haunted House

Dickens’s 1859 Christmas “haunted house” turns out to be less about specters than about how rumor and memory haunt the living. A skeptical narrator debunks village frights and, in Master B.’s garret, meets the truest ghost of all.

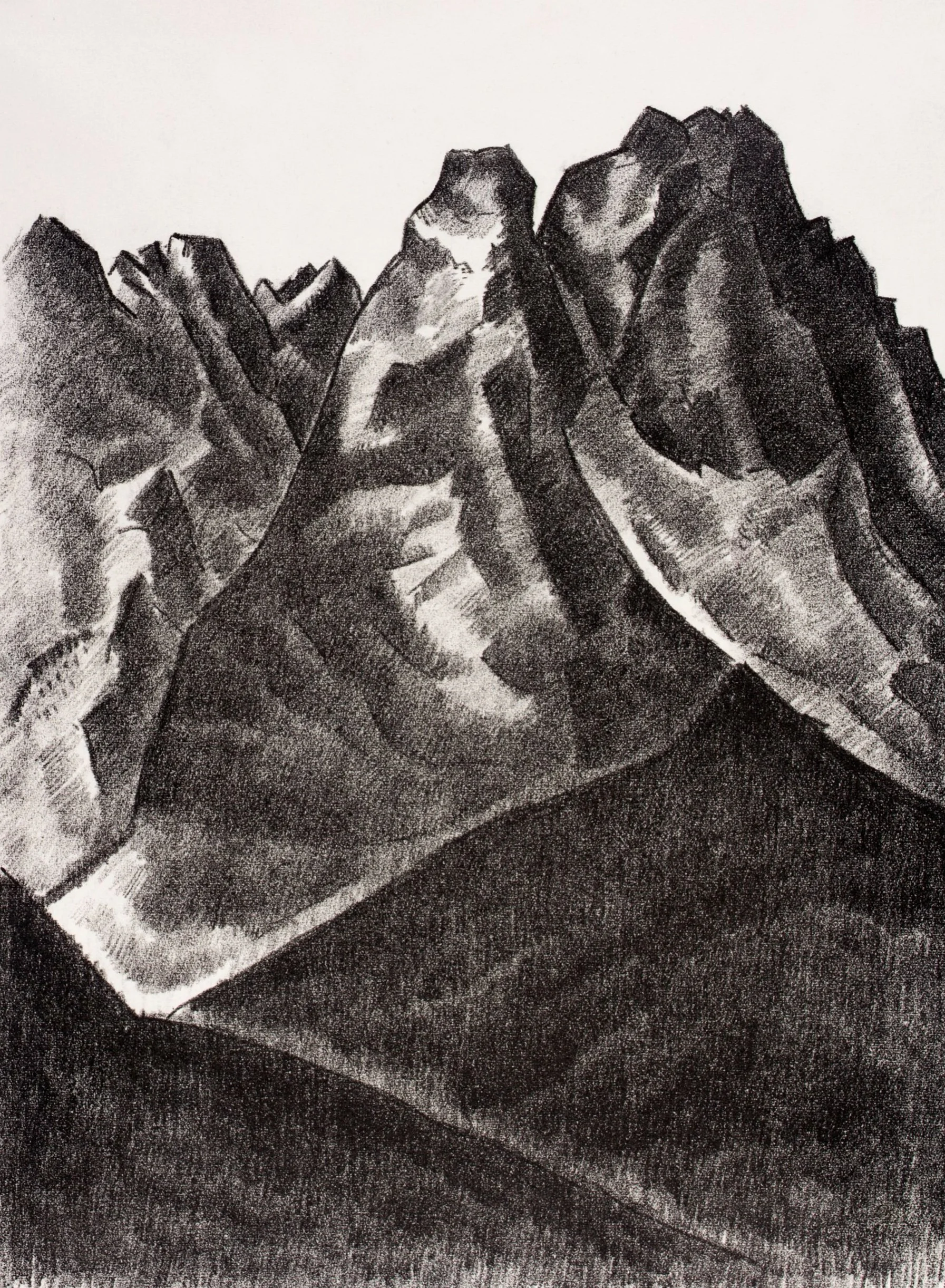

The Old Mansion

A grand seaside hotel once filled with gaiety, the Old Mansion fell into ruin after a tragic shipwreck, whispers of looted dead, and ghostly visions of drowned mothers and children. Today, only charred timbers and haunted memory linger on the dunes of Long Beach.

My Christmas Dinner

In contrast to the boisterous abundance celebrated in Dickensian feasts, this story lingers on the dissonance between expectation and experience, capturing the melancholy of a solitary holiday meal with understated precision. The author, unnamed, delivers a narrative that winks at Victorian propriety even as it peels back the veneer of seasonal civility.

The Chimes

Often overshadowed by A Christmas Carol, The Chimes is Charles Dickens’s sharper, more radical holiday tale—an indictment of institutional cruelty and moral complacency, wrapped in the eerie clang of spectral bells. Written in the wake of political disillusionment, it offers not comfort but confrontation, demanding that readers reckon with poverty not as scenery, but as scandal.

Impressions of an Indian Childhood

In Impressions of an Indian Childhood, the opening chapter of American Indian Stories, Zitkala-Ša renders a vivid and tender portrait of life on the Yankton Sioux reservation through the eyes of a child, infused with sensory detail, matrilineal intimacy, and the subtle tension of a world soon to be disrupted.

Thanksgiving Day

In Thanksgiving Day, Ambrose Bierce strips the holiday of sentiment and reveals its moral hollowness, turning the ritual of pardon into a grim spectacle of irony and injustice. With characteristic venom, he exposes a society eager to pat itself on the back for mercy only after indulging fully in cruelty, a feast of self-congratulation served cold.

The Man with the Book

In The Man with the Book, a pivotal early chapter in The Witch of Salem, John R. Musick conjures a spectral figure whose cryptic presence haunts both the colonial landscape and the conscience of its people. Neither wholly allegorical nor entirely human, he embodies the uneasy fusion of religious zeal and retributive justice that drives the Salem trials forward—his silent authority casting a longer shadow than any spoken curse.

Howe’s Masquerade

In Howe’s Masquerade, one of the more allegorical tales from Twice-Told Tales, Hawthorne stages a spectral procession of America’s past within the ballroom of Boston’s Province House, blurring the line between revelry and reckoning. Cloaked in historical costume and moral unease, the tale reflects Hawthorne’s preoccupation with the haunted legacy of the Puritan past and the theatricality of national identity.

To Be Read at Dusk

In To Be Read at Dusk, published in the Christmas issue of Household Words, Dickens departs from his usual moral terrain to conjure a brief, unsettling meditation on fate and foreboding. Framed as a twilight conversation among travelers, the tale unfolds like a whispered ghost story—unresolved, uncanny, and lingering in the mind like a half-remembered warning.

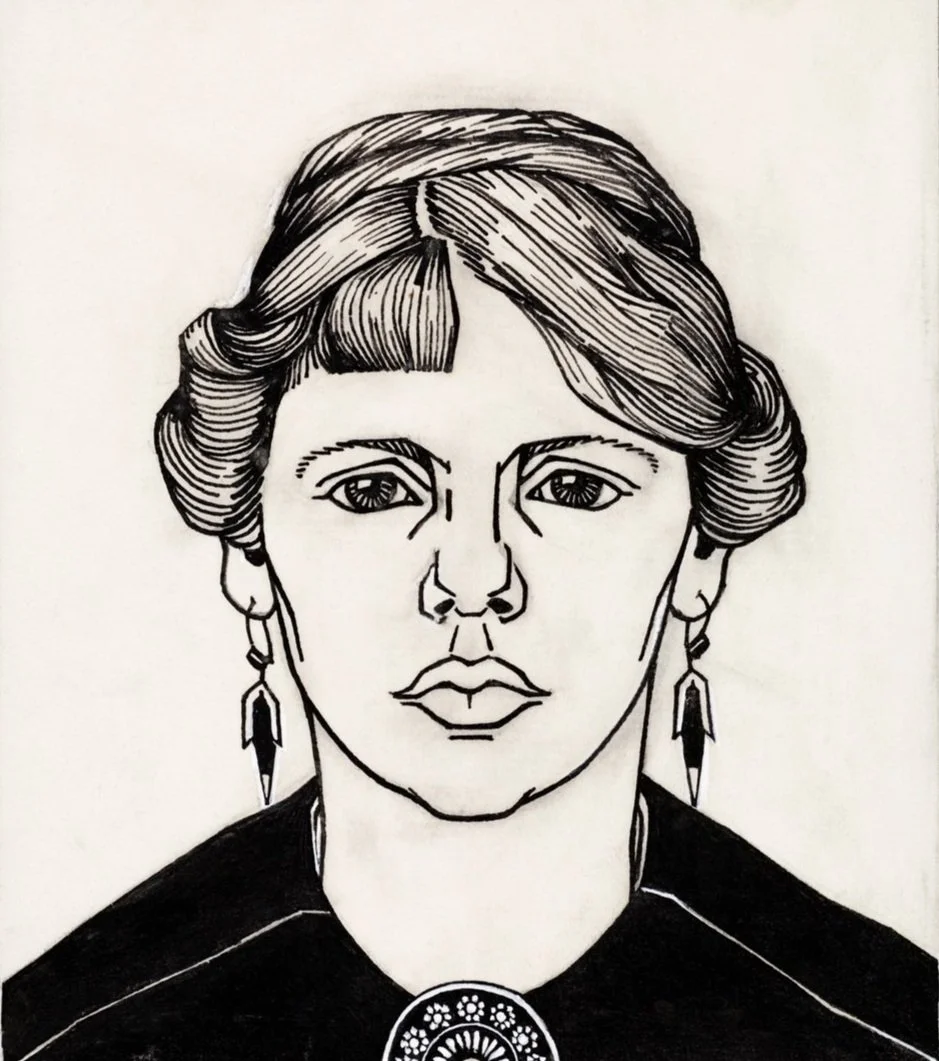

Aspasia: The Younger Feminists

Here Dora Russell reclaims the figure of Aspasia not as a mere consort of Pericles but as an intellectual foremother—bold, articulate, and dangerously ahead of her time. Russell uses Aspasia as both symbol and catalyst, drawing a lineage between ancient defiance and the modern feminist struggle for autonomy, education, and the right to shape public discourse.

Artemis: The Early Struggles of Feminism

In Artemis: The Early Struggles of Feminism, Dora Russell summons the goddess not as mythic huntress but as a symbol of untamed female independence, channeling her into a broader meditation on the earliest eruptions of feminist resistance. The chapter traces a lineage of rebellion—quiet and forceful alike—against patriarchal confinement, casting Artemis as both metaphor and precedent for the fierce, often solitary path carved by women demanding more than silence.

Jason and Medea: Is there a Sex War?

In Jason and Medea: Is There a Sex War?, Dora Russell revisits the ancient myth not for its romance or tragedy, but as a searing parable of betrayal, power, and the persistent asymmetries between men and women. Through the volatile figures of Jason and Medea, Russell probes the psychological and structural roots of gendered conflict, suggesting that the so-called "sex war" is less a battle than a reckoning centuries in the making.

Woman as a Supernatural Being

In Woman as a Supernatural Being, Richard Le Gallienne offers an ethereal vision of femininity untethered from earthly concerns—casting woman not as subject but as symbol, an ineffable presence glimpsed through poetry, myth, and moonlight. What emerges is a fin-de-siècle reverie that flatters even as it confines, revealing more about the author's longing for transcendence than about women themselves.

Cheap Knowledge

In Cheap Knowledge, a quietly elegiac essay from Pagan Papers, Kenneth Grahame pays tribute to the humble delights of secondhand bookstalls, where faded volumes whisper of forgotten owners and half-remembered dreams. With characteristic charm and a touch of wistfulness, he elevates the act of browsing cast-off books into a celebration of democratic intellect—where wisdom, once costly, is scattered like autumn leaves for any wanderer to claim.